A New Balance

Fotos von Mareike Tocha

Text von Miriam Stoney

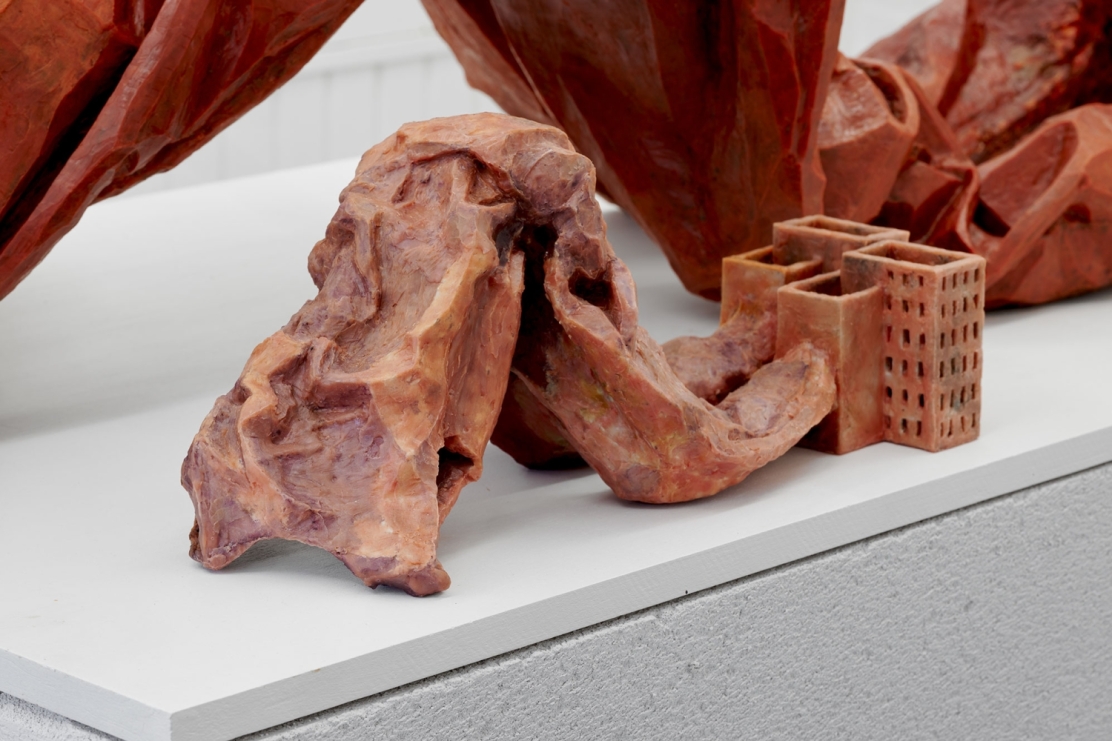

As a child, I was once instructed to draw a body without a skeleton. I proceeded to sketch out the girl’s figure in profile: she was in a state of toppling, legs having given way, her arms not bent but folded underneath her chest to cushion the blow from the fall. I must have imagined the bones having been sucked out of her feet, the process of collapse starting in the lower limbs, now pictured just moments before its completion. I conjured my own physics for this fantasy, of course. In any case, the basic structure of her body remained indelible to me, not least because it was wrapped in the denim jeans and long-sleeved t-shirts I happened to wear on weekends. For my attachment to this certain body’s structural integrity, however, I was penalised. The teacher took my drawing as an exemplary failure and showed it to the rest of the class. ‘Without a skeleton,’ she said, ‘You, yes you, would be little more than a heap of flesh.’

In order that an absence might register, there must be a space in the imaginary that has been left vacant. I have thought about my bones a lot since that classroom shaming.

But this space need only be a rough, notional outline – a crumpled pillow, for instance, might delineate the space where a head once lay. Albrecht Dürer’s Self-Portrait at Age Twenty-Two, c. 1493, conflates the artist’s perception of his own bodily thingness with the study of objects for the training of his visual and manual skills. In addition to the pillow sketched beneath the artist’s countenance and his left hand, on the verso of the Self-Portrait is a drawing now titled Six Pillows, described by Joseph Leo Koerner as a ‘sheet with six studies of crumpled pillows. Except for the top two, no pillow overlaps another, nor do they cast shadows on any surface outside their own. Unadorned and silhouetted against a neutral ground, each pillow is captured in its volume and coherency as a separate object, even as it is distorted from its essential square form. A pillow is the simplest of things: two surfaces enclosing a volume.’ But the pillows are also animated by their reverse: the artist’s self-portrait, his juvenile nose that was once nestled into their creases, his hand contracted as though caught in a tense reverie.

(A crumpled jacket, this wrinkled trouser leg. I look at the pile of clothes on the floor by the bed and (writely or wrongly) I identify: my, or, a self (or, the constituent parts thereof). Not only is the pile of clothes missing a wearer, but the wearer is also missing a pile of clothes. ‘Get me a Vomex,’ I groan, ‘It turns, inside. It turns out, that the skeleton crawls out by the mouth.’)

Koerner regards this as a form of prosopopoeia (figuring an address through another person or object). The metaphorical aspect of the soft furnishing as likeness, the transference of features onto cloth – not quite akin to the indexical trace of Veronica’s veil, smeared with Jesus’ countenance – is perhaps an attempted animism by which we share our characteristics with the world of objects. From the pillow to the bed to the bedroom to the house, through prosopopoeia we learn to distribute the sensible across bodies, to feel our weight spread across the material world, to see the imprint of an anthropomorphism.

In discourses around the ratification of the Anthropocene as a geological epoch, the weight of cities, buildings, infrastructures and other structural bodies became a quantitative indicator of the force we humans exert on the Earth. The weight of human activity once had other ethical inflections, however. Gravitas, as one of the Roman virtues, conjures weight as a measure of sincerity and thus dignity; a force by which mere men become citizens and statesmen. Hubris, on the other hand, is a kind of substance without weight. It was on account of her hubris that Leto sent Apollo and Artemis to slay Niobe’s numerous children. Having boasted of her bountiful fertility, the goddess took the lives of Niobe’s offspring as a means of shifting the balance of creative and destructive power between mortals and deities. Niobe reads as a figure of maximal life in a regime demanding more careful sustenance, a Malthusian scapegoat whose kids must be sacrificed to some greater value.

A pile of bodies, limbs prostrate and skin flayed. The gravitas of death and dying is difficult to topple. Mourning her children, Niobe is said to have turned to stone. But in this account, having her turning to stone is perhaps one way of granting the mother her weight. She is subject, subject to the forces enacted upon her. Like a mighty pine, she is fell. Like the erstwhile angel, she is fallen. And like any diabolical woman, she is pleasing. In powerlessness we have greater weight, we are most revered when we are at rock bottom.

Is this a parable about the problem of being taken seriously?

Is this a cartography of where we once were and can no longer be?

Is this a history of art in deliberate absences?

(My skeleton has since been replaced by the statue of Niobe that did not feature in the sanctuary to venerate the founders of Thebes. So it is that I walk upright and with structural integrity – until I don’t.)

The exhibition »A New Balance« is funded by Flanders State of the Art and the City Centre District Council, Cologne.